The start

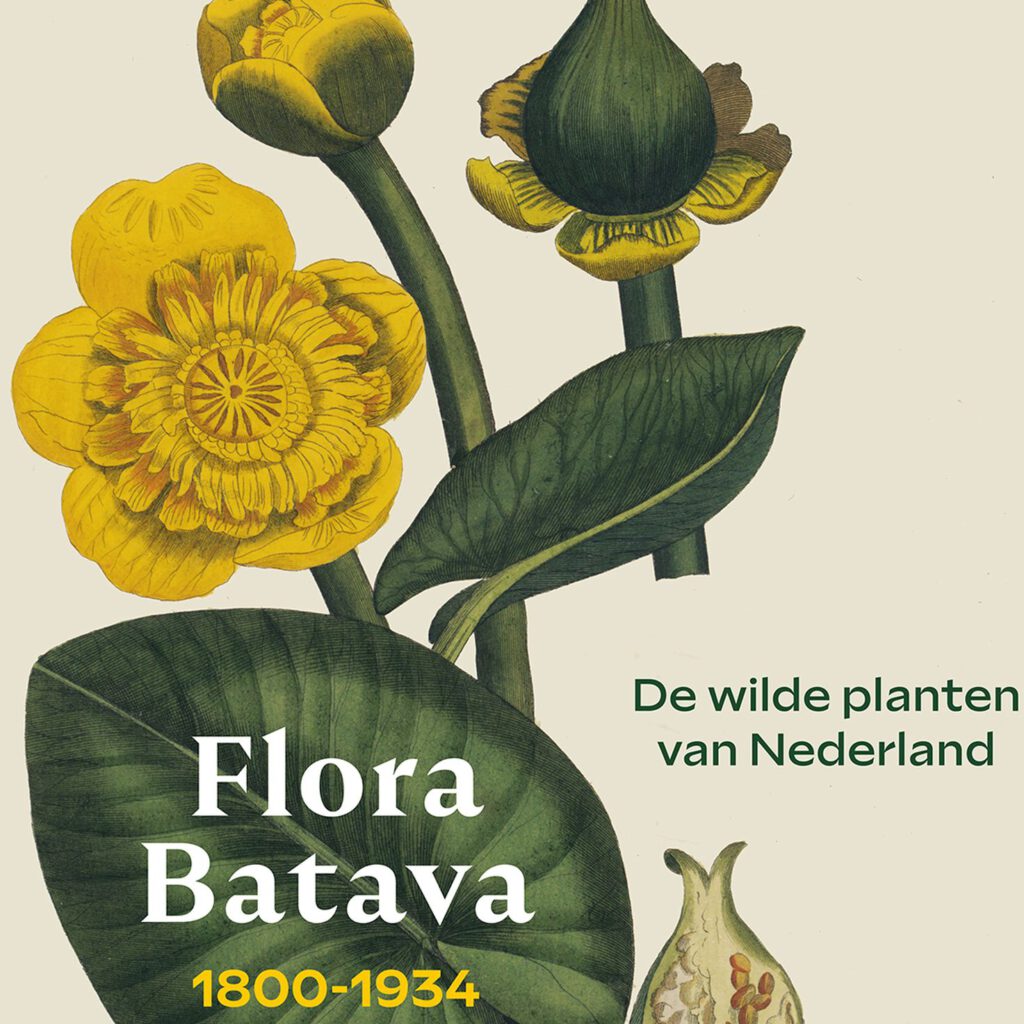

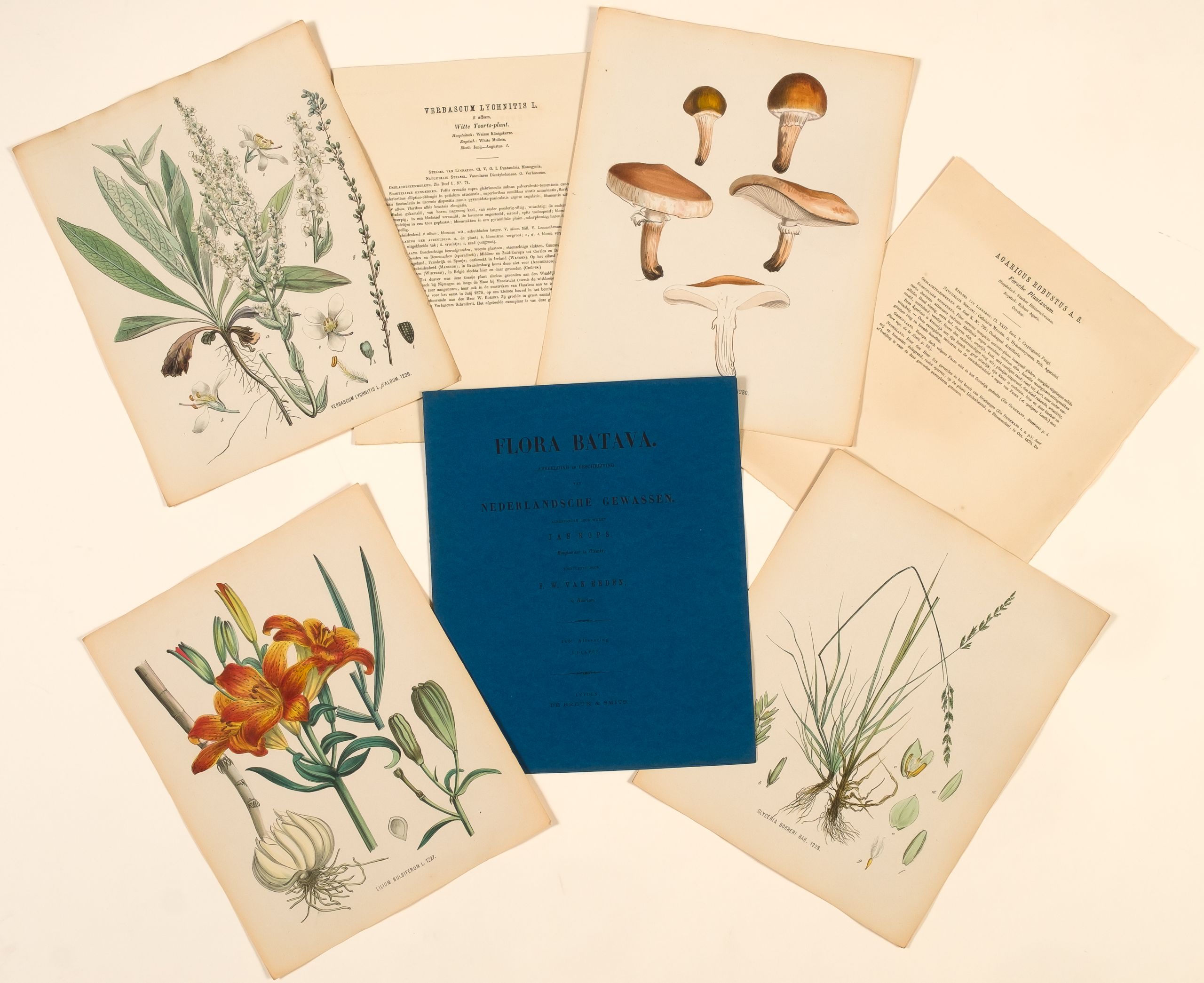

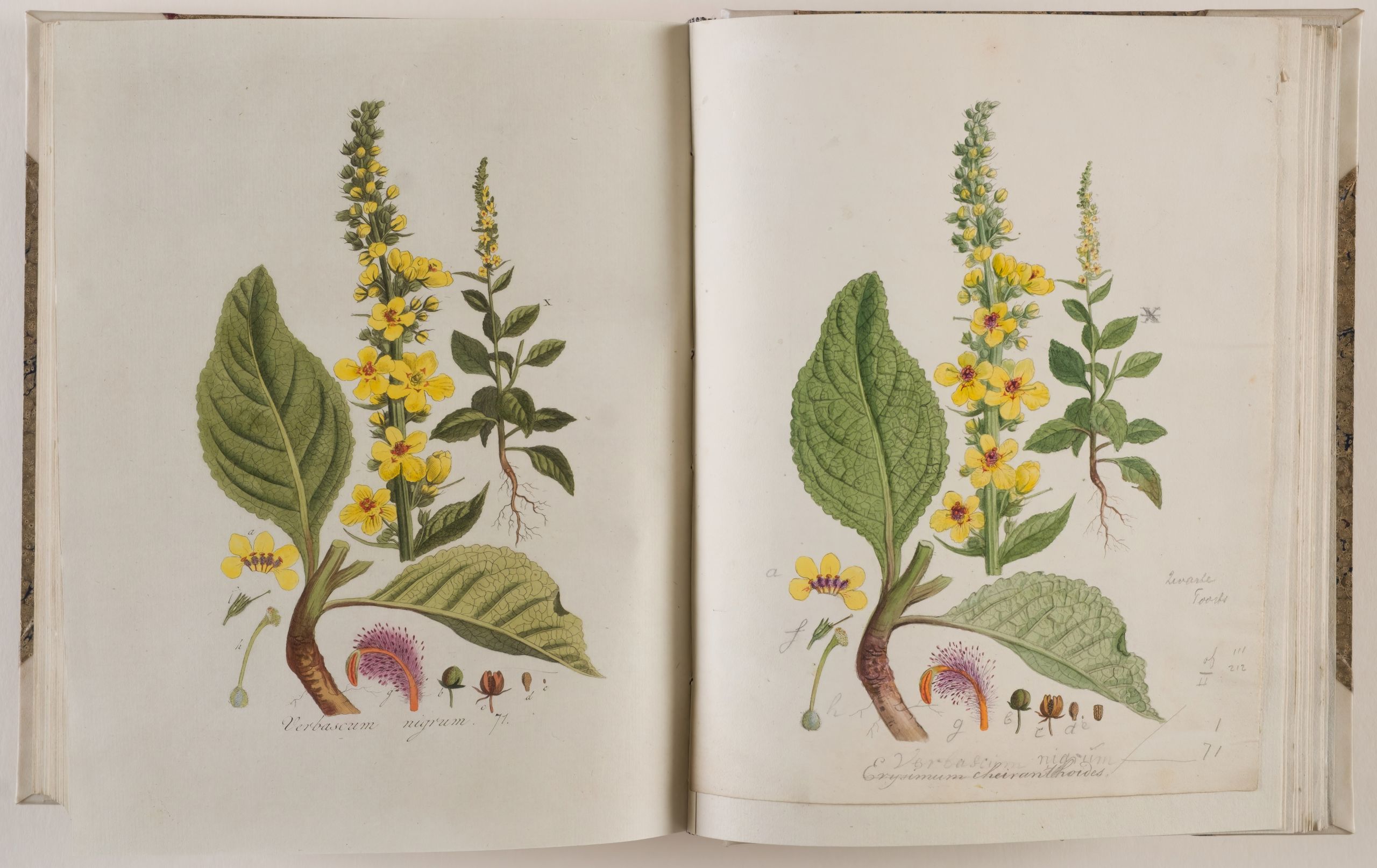

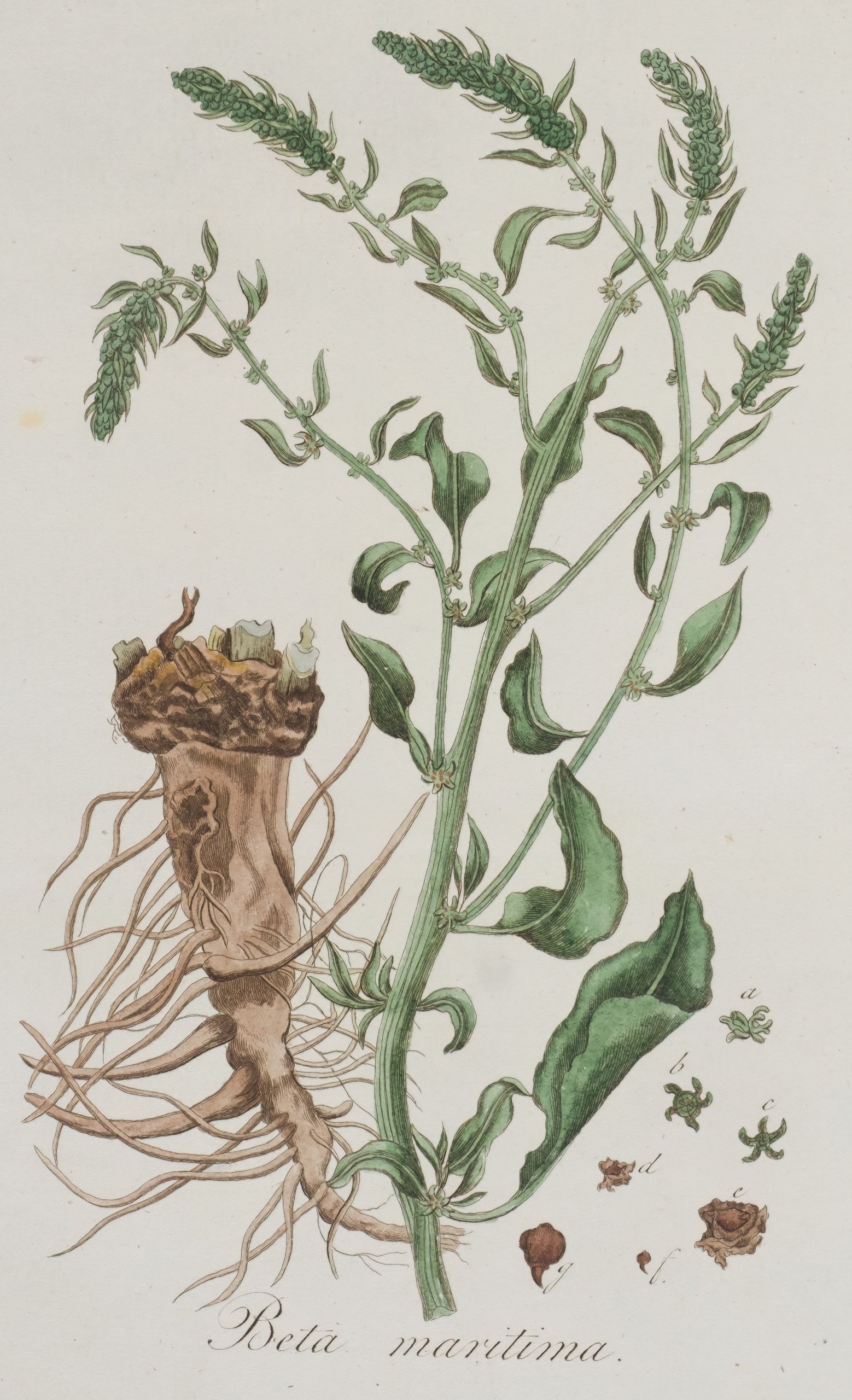

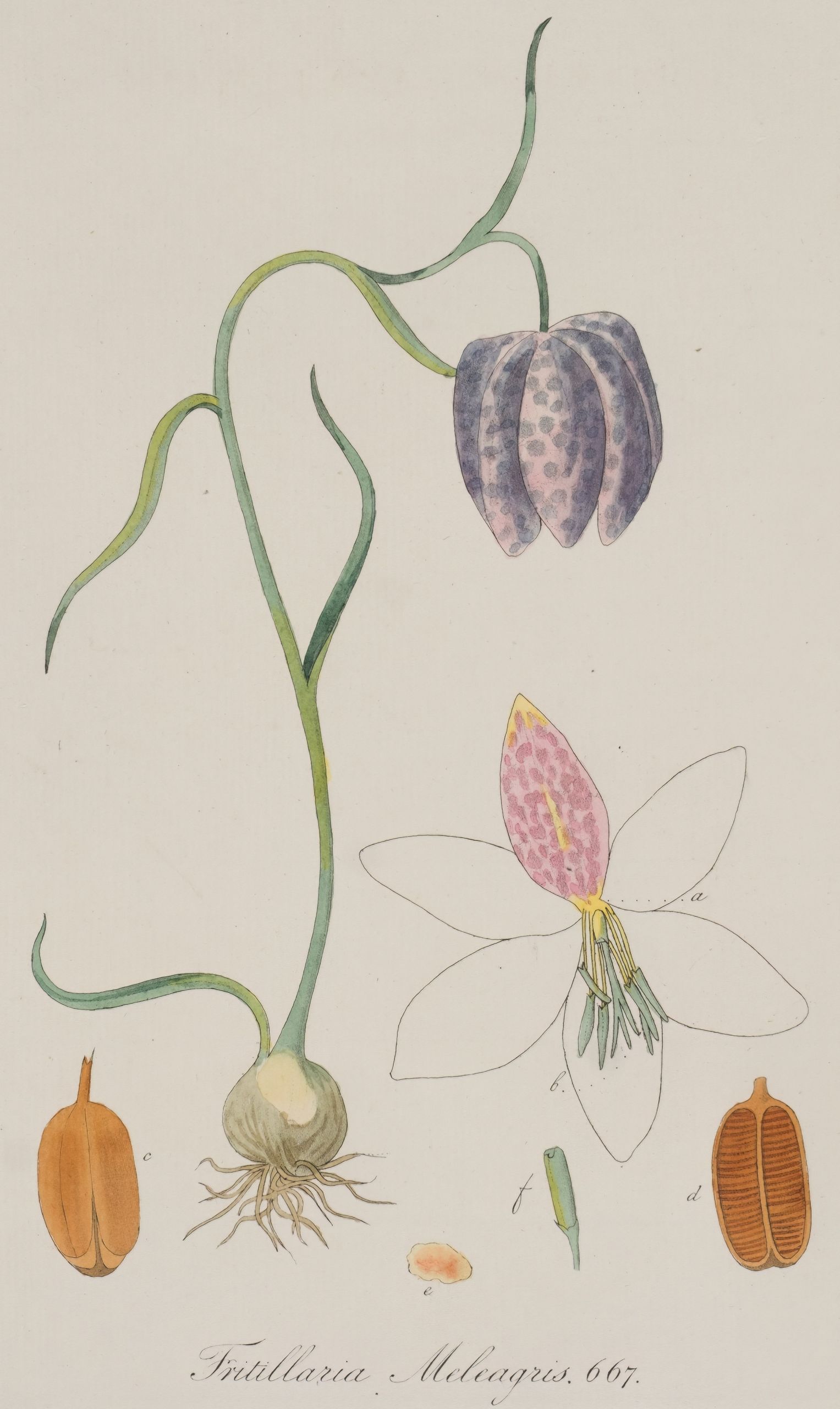

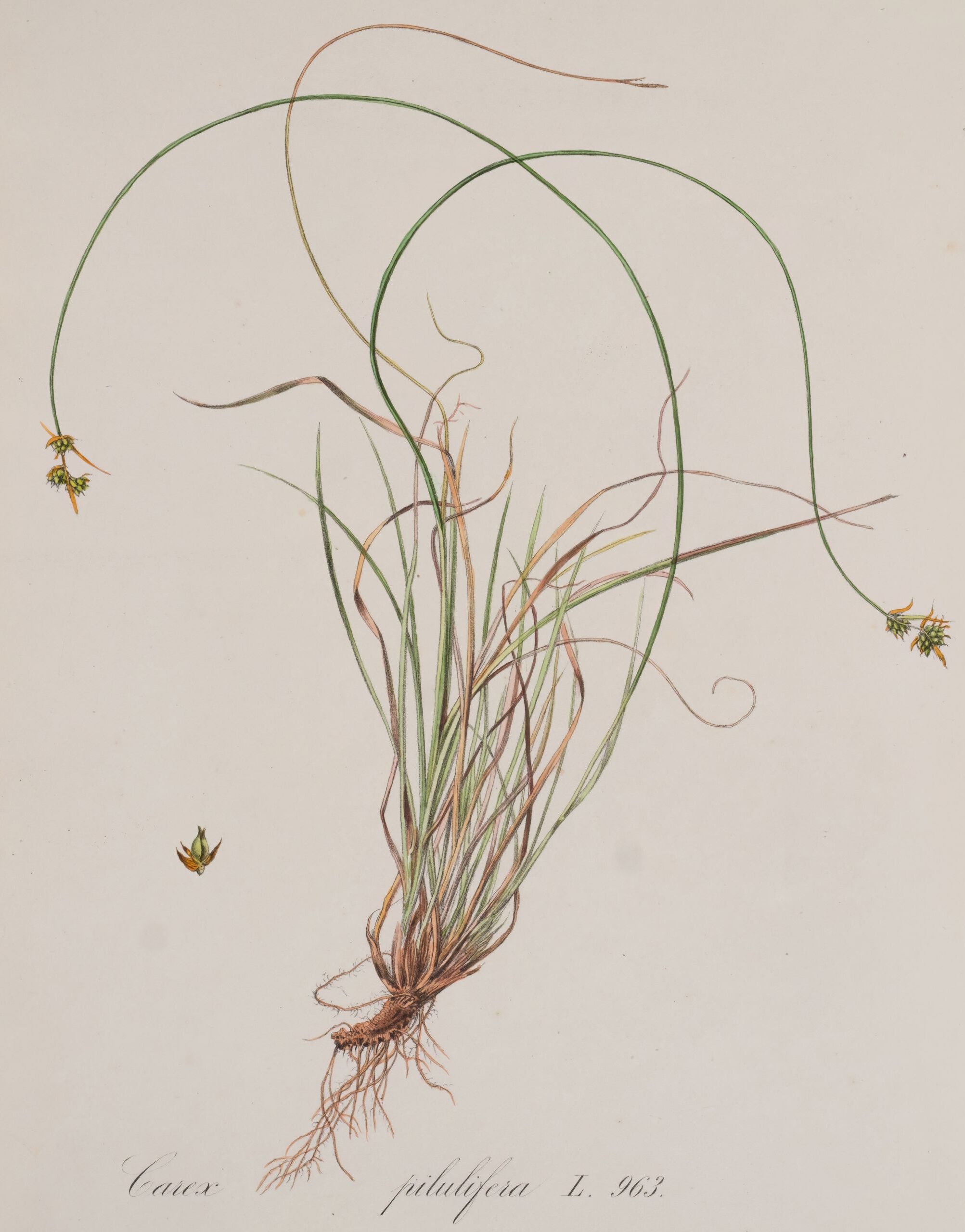

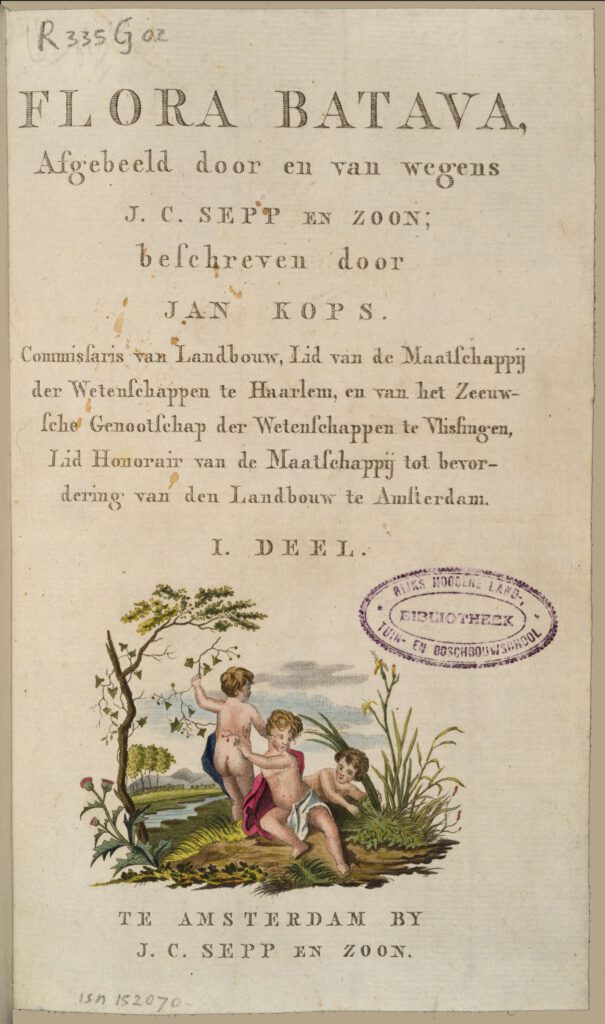

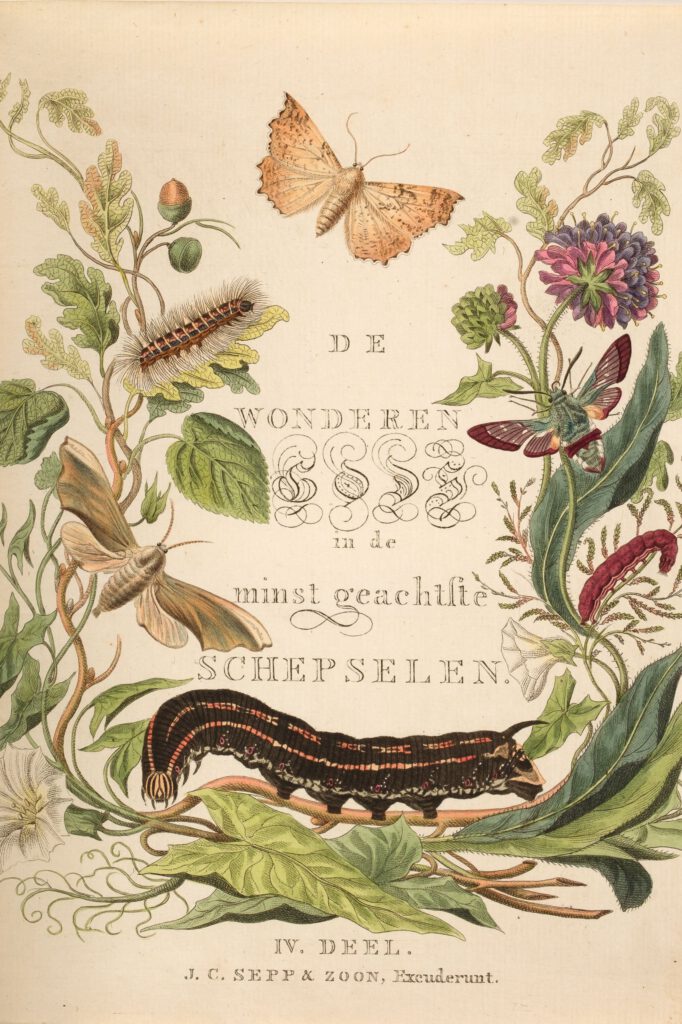

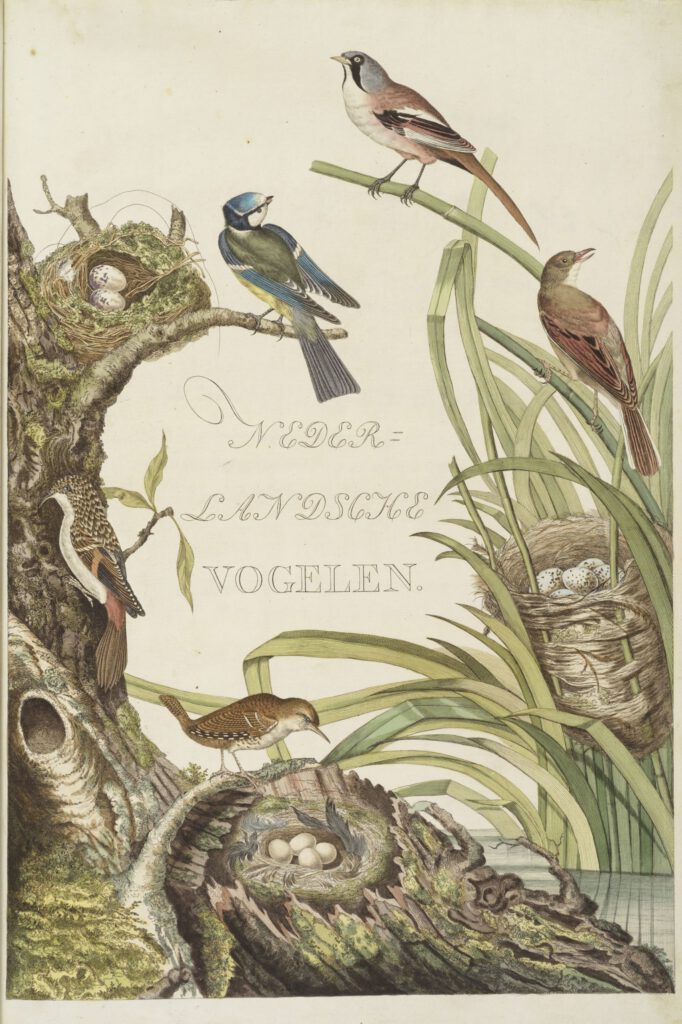

The idea for the Flora Batava, an illustrated serial publication describing all plants in the wild in the Netherlands, came from the publisher family Sepp, a publisher also known for publishing serial works about birds (Nederlandsche Vogelen, 1770-1829) and insects (Beschouwing der wonderen Gods…, 1762-1860).

The father of Jan Christiaan Sepp (born around 1710 in Goslar) was interested in physics and biology. He built his own instruments to study insects and started drawing insects at a young age. In the 1730s, he moved to Amsterdam.

In Amsterdam Sepp worked as a draftsman and engraver, creating land and sea charts. He was also well known for his knowledge of entomology. Together with his son Jan Christiaan Sepp (1739 – 1811) he collected and bred insects. Their butterfly cabinet with drawers for storing butterflies can still be seen in the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave in Leiden. In 1762, Beschouwing der wonderen Gods, in de minstgeachte schepzelen : of Nederlandsche insecten, …. about Dutch insects appeared, containing insects accurately drawn from life, engraved in copper and hand coloured. This work appeared in installments that could later be bound into volumes. Sepp created the first 30 plates with descriptions alone, after that he worked together with his son, who established himself as a publisher.

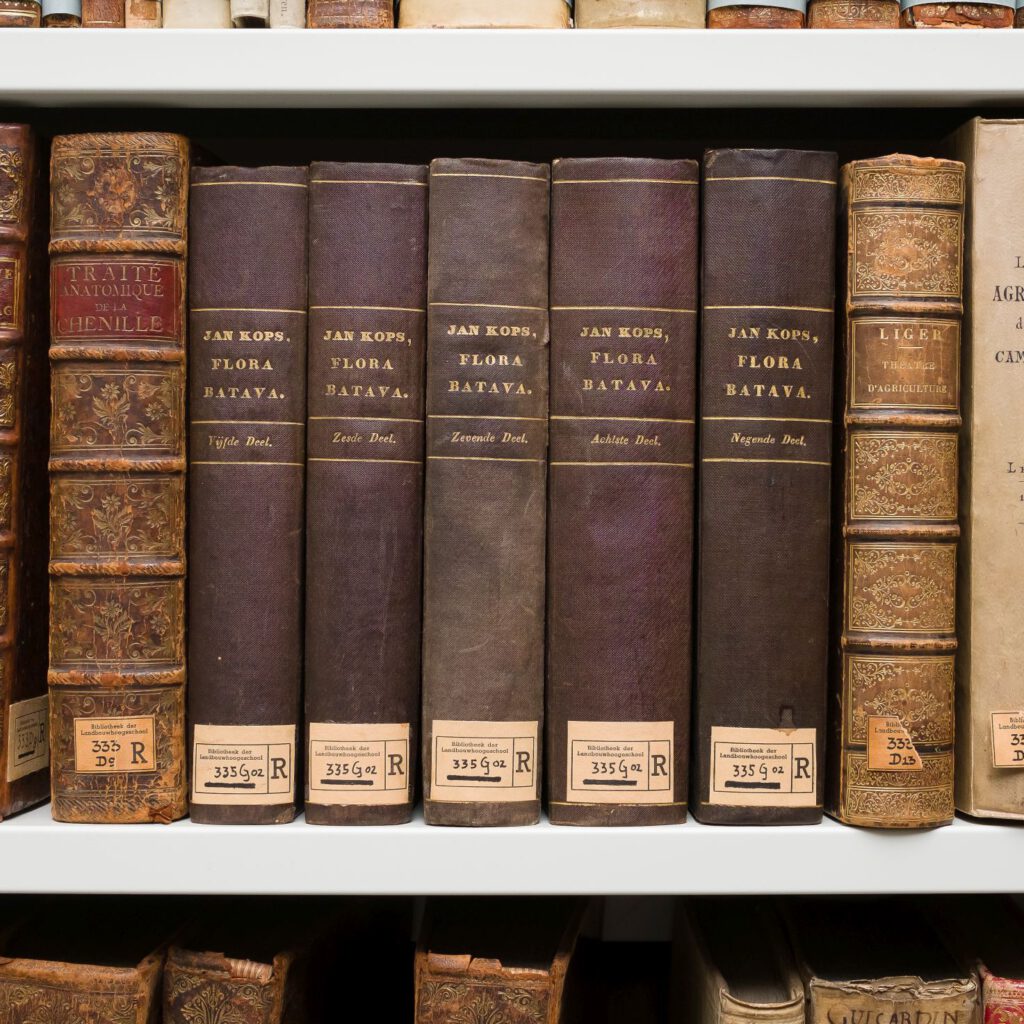

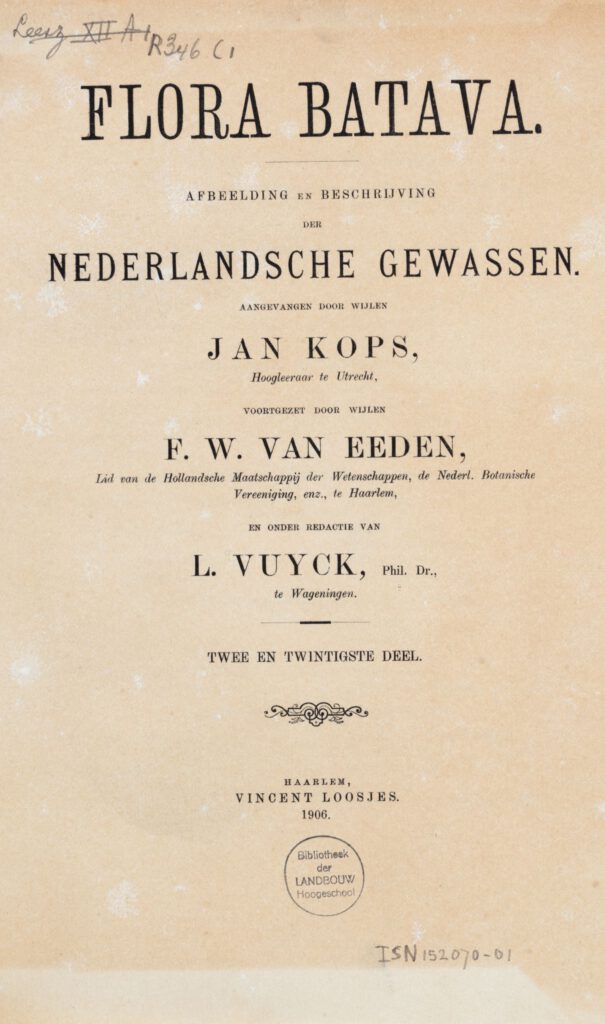

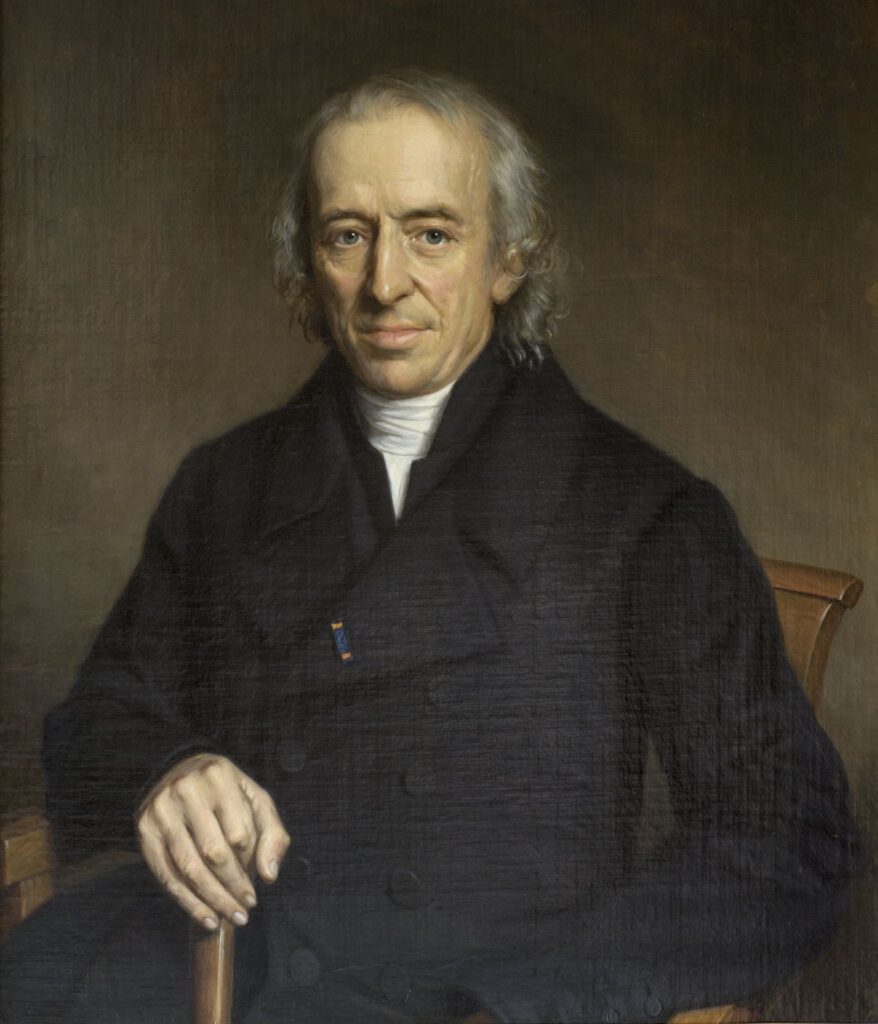

Jan Kops became the first editor of the Flora Batava. At the time Kops was the Commissioner of Agriculture at the National Economy Agency as well as an experienced and enthusiastic botanist.

The Anabaptist Jan Kops (1765 -1849), originally a theologian, was fascinated by botany from an early age. Despite this, his professional career mainly focused on agriculture. Until the Batavian revolution, Kops was only allowed to practice a theological profession, but after 1800 he started a civilian career.

In 1800 he was appointed “commissioner for the affairs of agriculture” at the agricultural department of the National Economics Agency in The Hague. In 1811, on his initiative, a Cabinet of Agriculture was established, first in Amsterdam and later in Utrecht.

In addition to his career in agriculture, Kops also remained active in the field of his beloved botany. He accepted the publisher Sepp’s request to become editor of the Flora Batava and dedicated himself to this publication for almost 50 years. However, he accepted this position under certain conditions which he comments upon in his biography.

“Maar ik verlangde een ander plan, dan dat van Sepp te volgen. Ik wilde geene kopyen, maar oorspronkelijke afbeeldingen leveren. De planten moesten van den vaderlandschen grond zijn genomen, hetgeen voor eene inlandsche Flora volstrekt noodzakelijk is. …”

From: J. Kops, Levensberigt betrekkelijk mijne werkzaamheden voor het publiek en hetgeen hierop invloed had (1839)

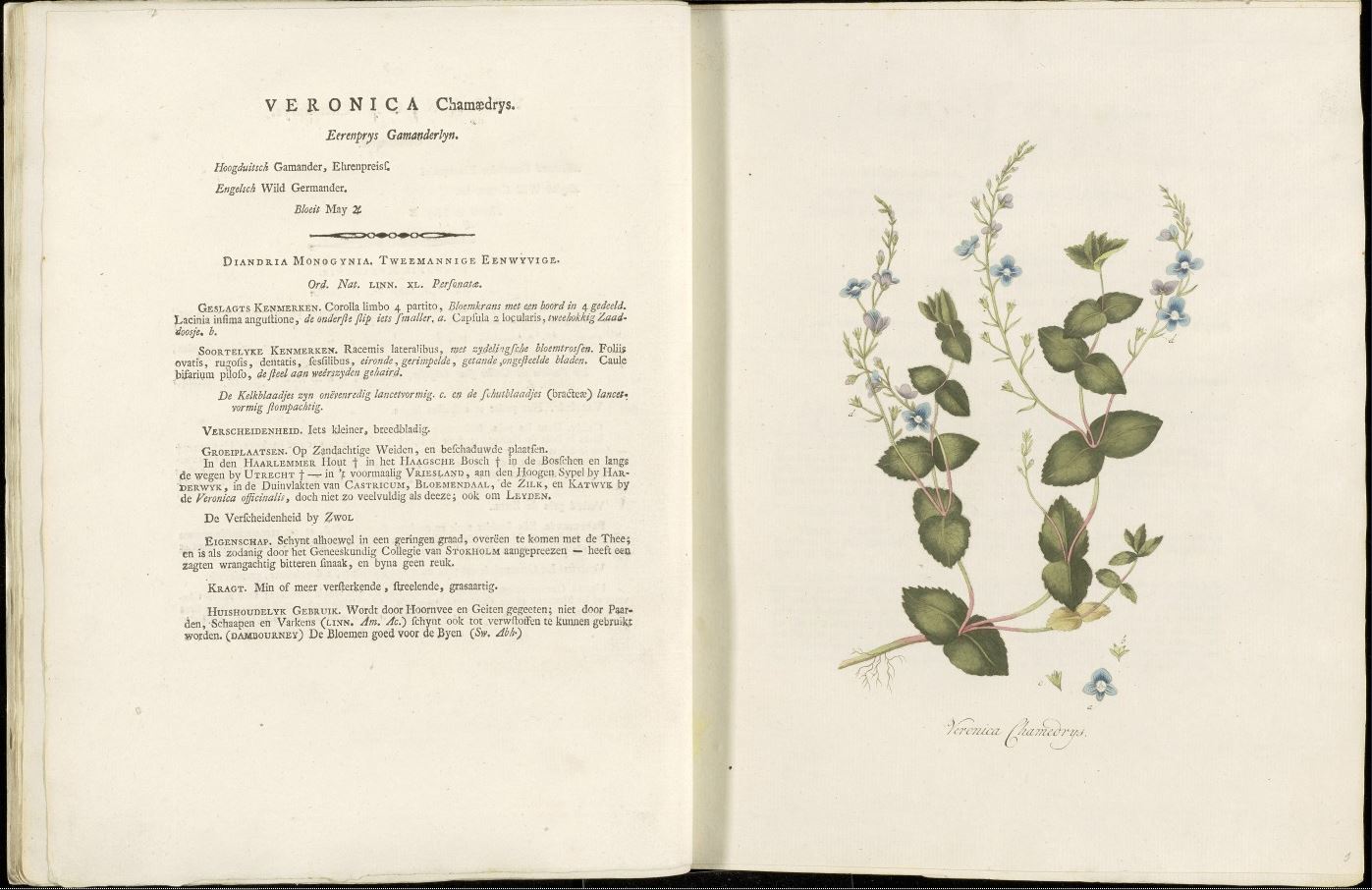

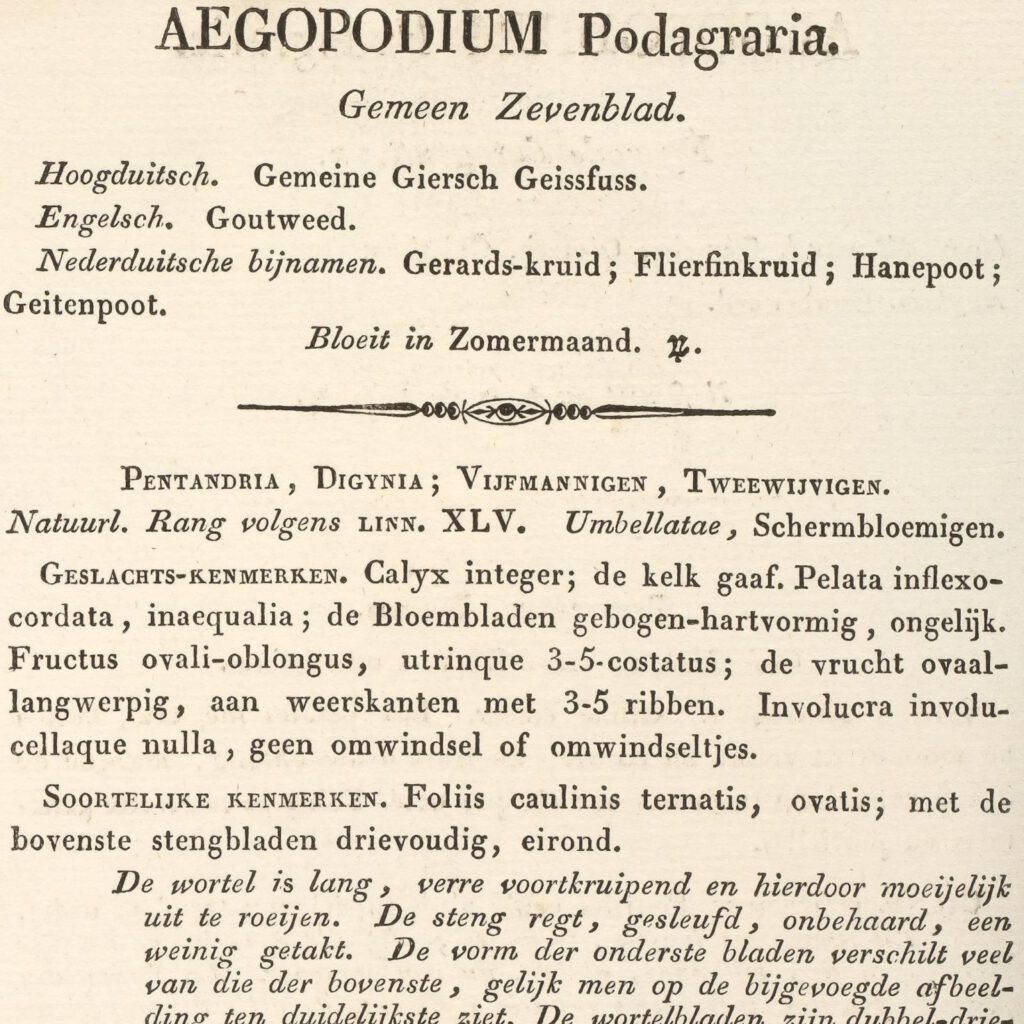

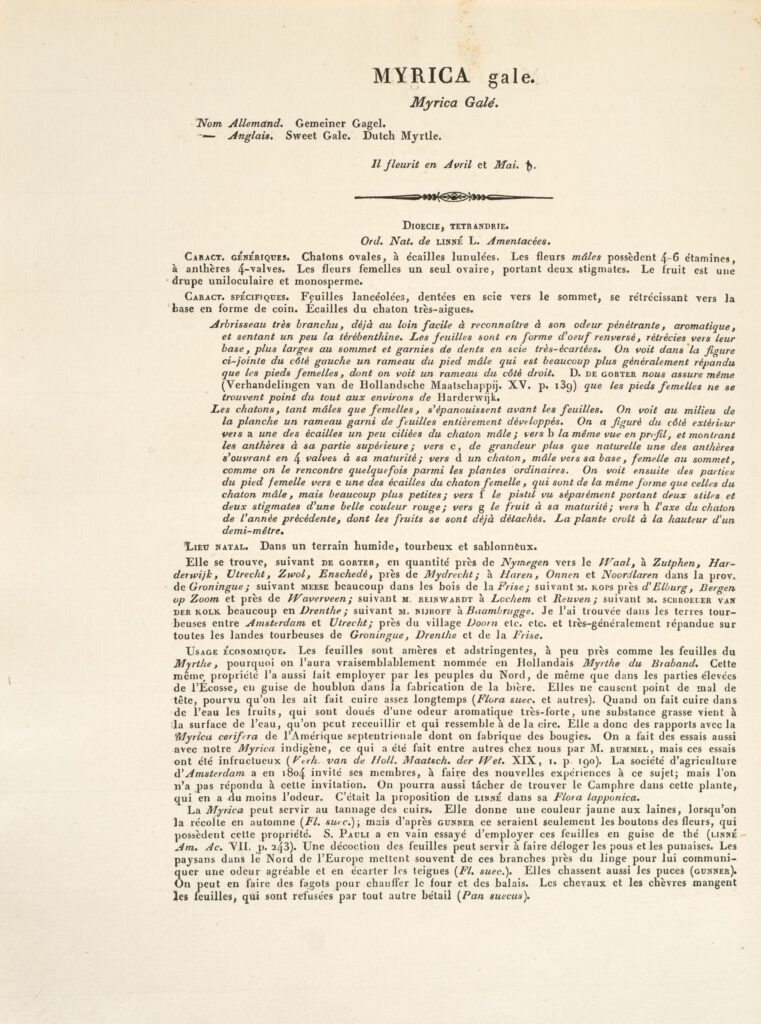

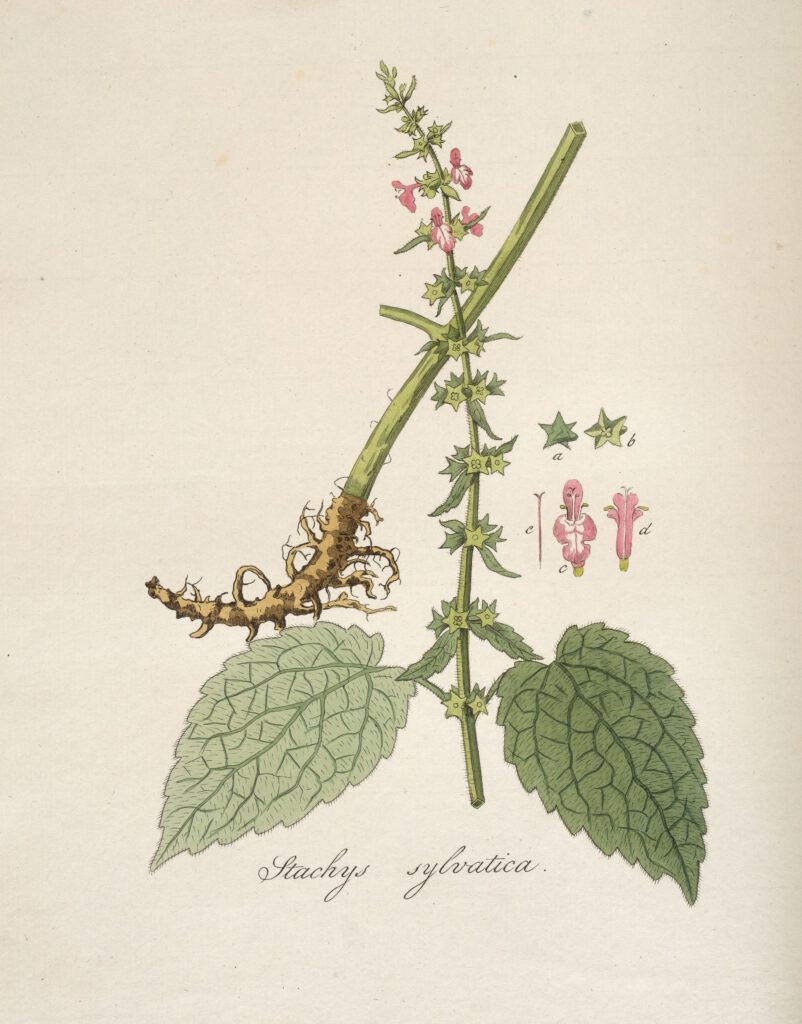

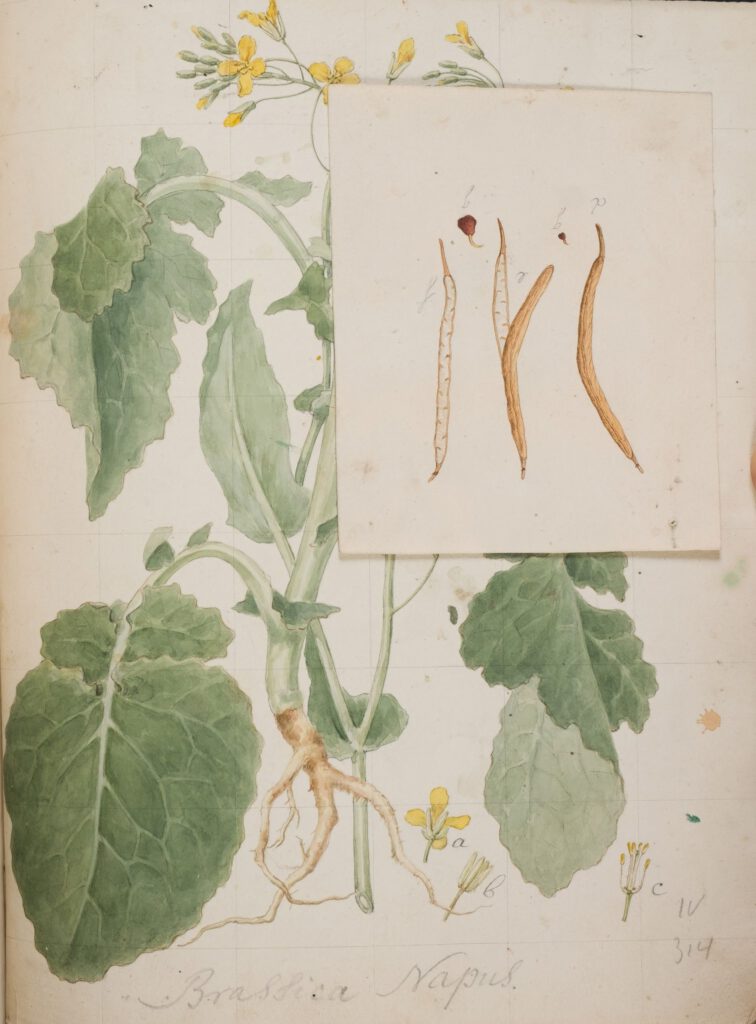

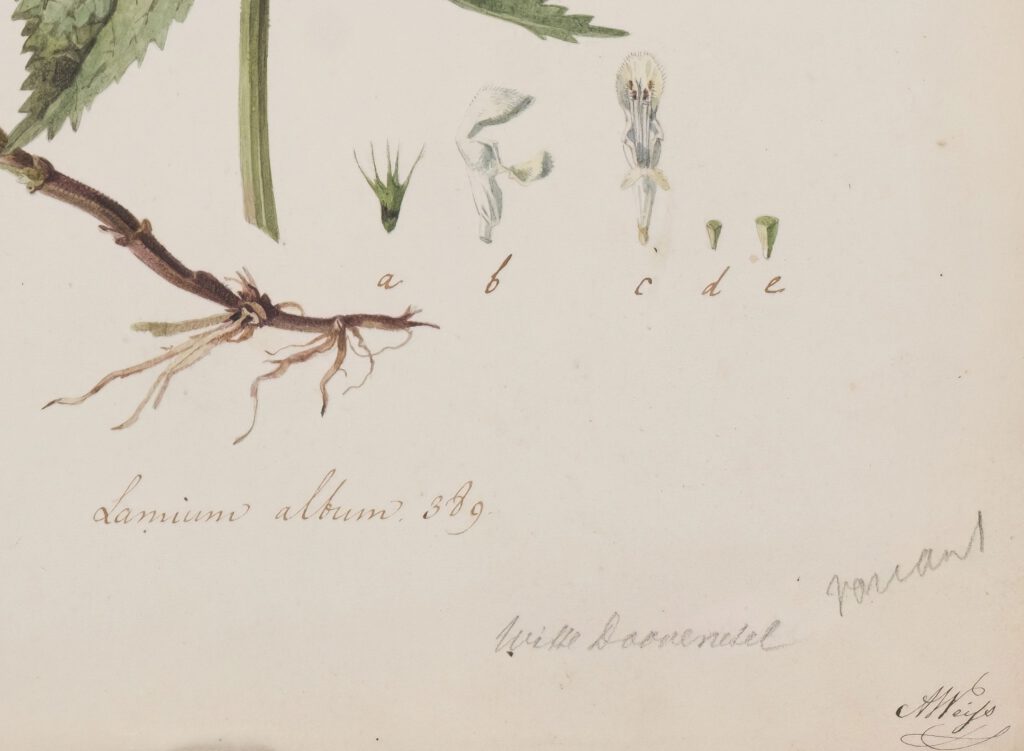

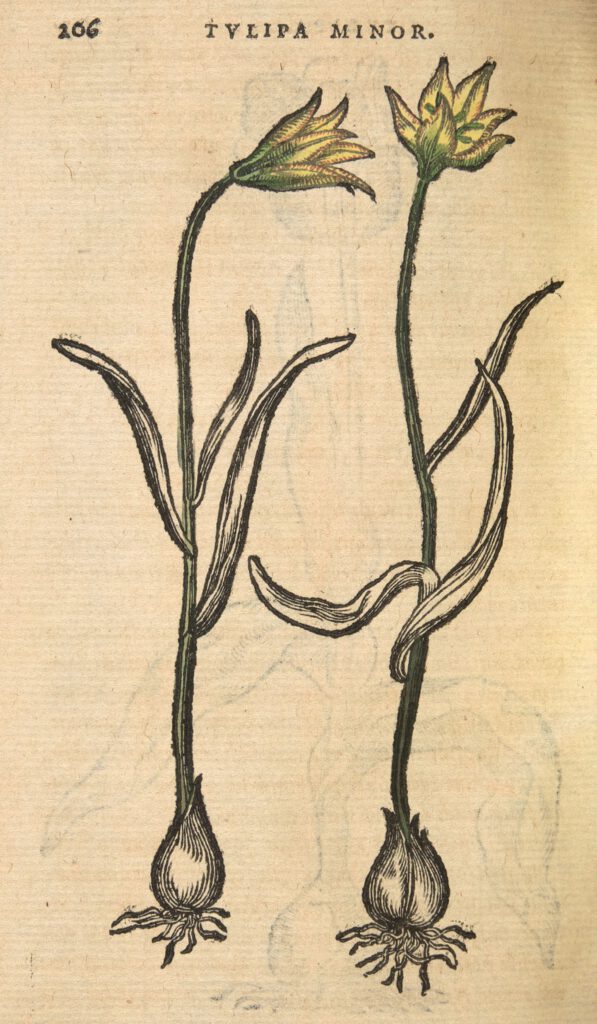

In his biography, Jan Kops writes that he did not agree with Sepp’s idea of using foreign publications for the drawings of the Flora Batava. The first 40 drawings for the Flora Batava were taken from the Flora Londinensis by William Curtis. However, Kops wanted the plants to be drawn from Dutch flora. And so it happened, local specimens were collected and used for the plant descriptions from plate 41 onwards. The collected plants were used as examples by the botanical artists, whose drawings serve as an example for the engraving and the final colouring of the prints.

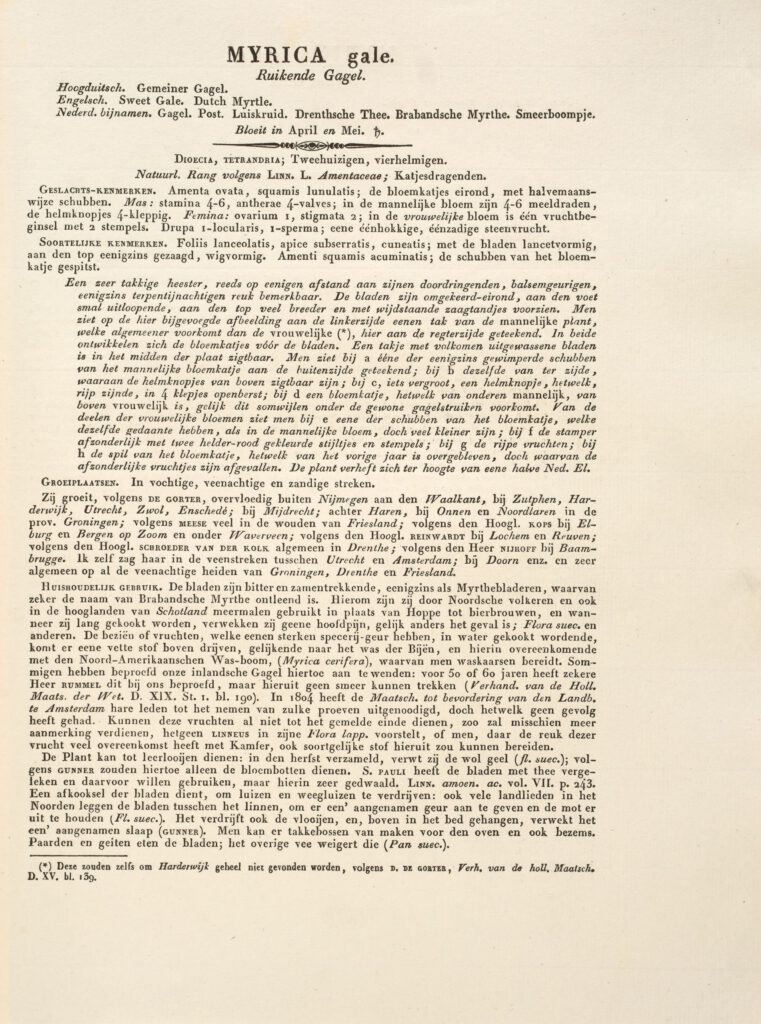

But Kops had more ambitions: he also wanted the native plants to be described in a scientific, understandable and useful way. The plants were described according to the system of Linnaeus and then Dutch names and folk names were also added. Descriptions were made in Dutch and in French and information about the practical applications of the plants was included.